top of page

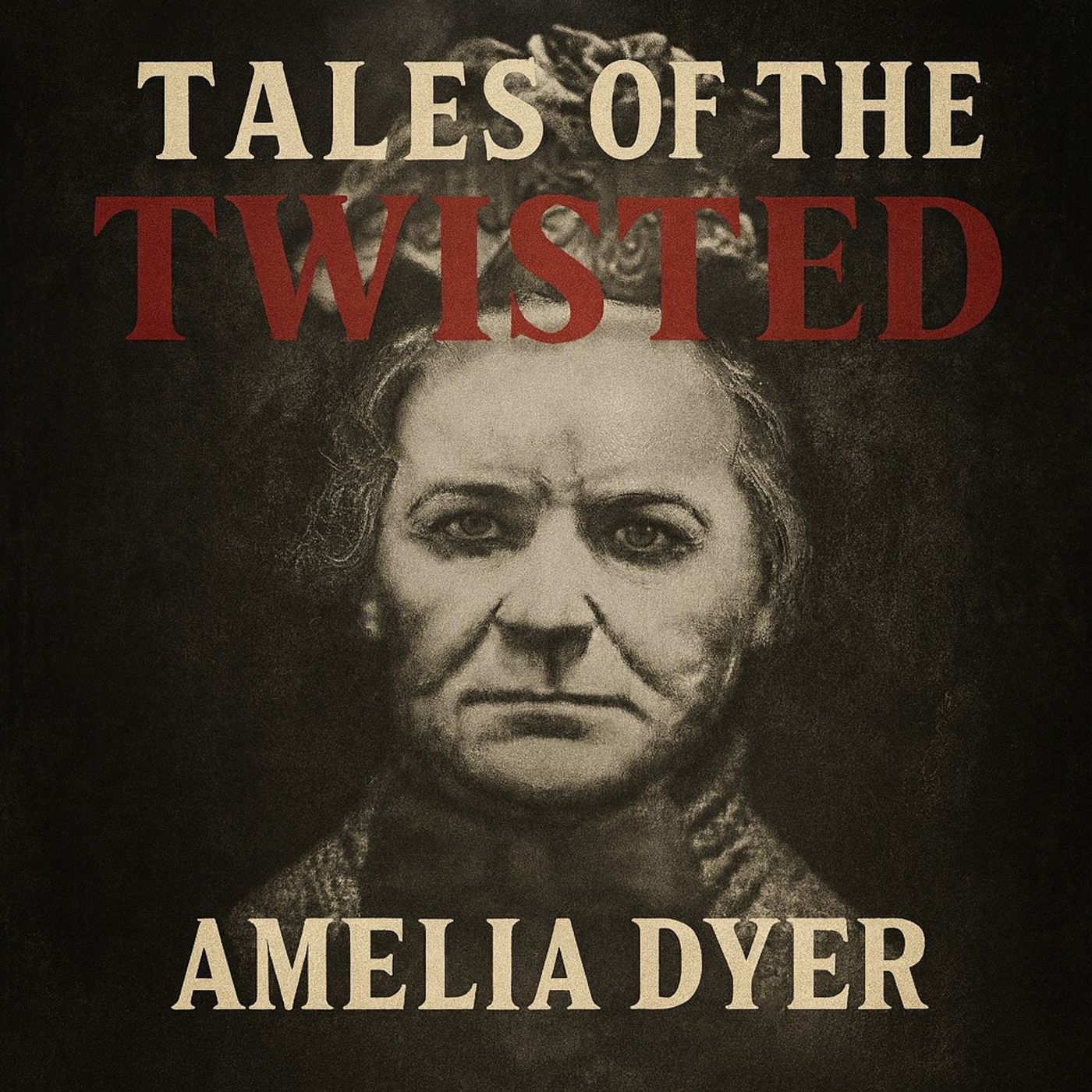

Tales of the twisted

podcast

Amelia Dyer: Britain’s Baby Farmer Killer

Episode Title:

Full Transcript

The garden behind the small cottage in Reading was quiet, overgrown, untouched, forgotten. It was the early 1900s, and the new tenant was digging to clear space for a vegetable patch. The soil was dark and damp, clinging to the spade as he worked row by row.

But then came a sound that soil shouldn't make, a sharp, brittle crack. He knelt down and brushed the dirt aside. Small bones emerged, fragile, pale, unmistakably human. More digging revealed several sets, tiny remains, infants. The authorities arrived, baffled, but grimly unsurprised when they examined the property records. The cottage had once been occupied by a woman whose name, England, had not yet forgotten. They could not prove the remains belonged to her victims because early forensic science wasn't capable of such certainty. But investigators believed they had uncovered one more shadow of the woman already known as the most prolific baby murderer in British history. Her name was Amelia Dyer.

This is Tales of the Twisted. True stories of the strange, weird, bizarre, and eerie. Amelia Elizabeth Dyer was born in 1837 in Pile Marsh near Bristol. She grew up in a respectable working-class household. Her father, Samuel Dyer, was a master shoemaker. Her early life, however, was marked by trauma. Her mother suffered from severe mental illness, typhus induced, and Amelia, still a child, witnessed violent mood swings, hallucinations, and cognitive breakdowns. She spent years caring for her mother before Sarah Dyer died in 1848.

By age 11, Amelia had already experienced instability, illness, and the fear of losing control. After her mother's death, Amelia learned to read and write, rare for a working class girl at the time. She later apprenticed as a nurse and midwife, entering a profession built on trust, access, and vulnerability. It was during this period that Amelia met Elaine Dayne, a midwife who quietly taught her the dark economics of baby farming.

Baby farming had emerged centuries earlier as a social workaround because Britain had no social safety net. Unmarried mothers faced extreme stigma. Families disowned daughters for pregnancy outside marriage. Employers fired single pregnant women. Welfare systems did not exist. And adoption laws were non-existent. Women in crisis often placed newspaper ads seeking someone, anyone, to care for their infants. This created a system where caregivers could accept infants for a fee. Some acted responsibly, many did not.

There was no oversight, no inspections, and no legal requirements. In the Victorian slums, where disease, hunger, and poverty were constant, infant mortality was so common that a baby's death rarely raised questions. Into this world stepped Amelia Dyer. Amelia began offering lying in services, housing for unmarried pregnant women, delivering their babies, and taking payment to care for the infants or arrange adoptions. Some mothers never checked on the children again. Others wrote hopeful letters. Amelia rarely answered them. She discovered quickly that infants could die without suspicion. Doctors habitually recorded cases like stability from birth, lack of breast milk, convulsions, and baby farmers, good or bad, profited from the desperation of mothers who had nowhere else to turn.

By the mid 1870s, Amelia began using a wildly available product called Godfree Cordial, was also known as Mother's Friend. It contained opium and given consistently it sedated infants so deeply that they stopped crying, stopped feeding and slowly died of starvation. In overcrowded Victorian cities, a silent house attracted no attention. Eventually, the number of infant deaths tied to Amelia drew some concern. One doctor refused to continue signing her certificates and alerted authorities. A full investigation followed and in 1879, Amelia was convicted of neglect and sentenced to 6 months of hard labor. It was her first and only legal consequence until the end.

When Amelia was released, she returned to baby farming with a new approach. No more doctors, no more death certificates, no more paperwork that could link her to the bodies. Instead, she disposed of infants herself. She abandoned starvation for something faster and quieter, strangulation using white dress making tape. Later, she confessed, "I used the tape. It was my friend." From the early 1880s onward, Amelia killed infants within hours of receiving them. To avoid patterns, Amelia moved frequently. Bristol, Reading, Casham, Kensington, London's East End. She also used aliases, including Mrs. Harding, Mrs. Thomas, Mrs. Smith, Mrs. Mott. Each move brought fresh newspaper ads from desperate mothers and more infants who vanished without record.

The true number of victims is unknown, but historians estimate at least 50 confirmed, likely 200 to 400, possibly more given the number of years she operated. Infant mortality was so high and record keeping so poor that many deaths simply disappeared into the statistical noise of Victoria Britain. By the 1890s, a small number of mothers reported that they could not contact the woman who took their babies. But without national adoption laws, case tracking, or intercity communication, no one realized the scale of the operation.

Amelia Dyer was a ghost moving through a broken system and the system enabled her. On March 30th, 1896, a bargeman saw a package floating in the river Tames in Reading. Inside were two infants, a boy and a girl, carefully wrapped and strangled with white tape. Detectives examined the wrapping paper and found a faint but legible name and address tied to one of Amelia's former residences. It was the break they needed. Investigators placed a decoy newspaper ad requesting a baby nurse and Amelia responded almost instantly.

On April 3rd, 1896, officers intercepted her as she left her home to pick up a new infant. Inside the house, they found letters from dozens of mothers, clothing belonging to infants, opium preparations, white dress making tape, adoption advertisements, telegram records, and receipts showing payment for infant care. The smell of decomposition hung in the air, though no bodies were in the house. Investigators believe she had recently moved or disposed of them. Over the next weeks, police dragged sections of the tames and recovered additional infant remains tied to her operation. This time, the evidence was overwhelming.

Despite the number of bodies and complaints, prosecutors focused just on one murder, the case of baby Doris Archer, because the paper trail was strong, the evidence was direct, and it guaranteed conviction. The trial lasted just five hours and the jury deliberated for only 4 and a half minutes. Amelia Dyer was sentenced to death on June 10th, 1896. She was hanged at New Gate Prison and her last words were, "I have nothing to say." Amelia's crimes triggered national outrage.

The British public demanded reform and as a result, the Infant Life Protection Act was strengthened in 1897. Foster homes and adoption arrangements began facing inspections. Baby farming operations were now monitored. Classified ads for infant adoption came under scrutiny. Reformers fought for paternal responsibility laws. Her case exposed a gaping hole in Victorian society, one where shame, poverty, and a lack of oversight converged into tragedy. Years after Amelia's execution, the skeletal remains discovered in the reading garden reignited public fascination and horror. Authorities could not conclusively attribute the bones to her victims, but the location aligned with one of her former residences, and investigators at the time believed the evidence supported that likelihood. By then, her legacy was already firmly cemented.

A woman who used the cracks in society to commit one of the most horrifying series of crimes in British history. If you found this episode disturbing, thought provoking, or illuminating, be sure to follow and subscribe so you never miss a new story from Tales of the Twisted. And if you enjoy these deep, factual dives into history's darkest corners. Take a moment to rate and review the show. It helps me reach more listeners who crave these true stories of the strange, weird, bizarre, and eerie. Thanks for listening.

bottom of page